Patient Involvement in Clinical Trials: What’s Changed Over the Years

When Len Gardner was admitted to the NIH Clinical Center in 1955, he joined a clinical study that would ultimately save his life. Diagnosed with a serious kidney condition, he received an experimental drug—now known as prednisone—that hadn’t yet reached the medical community.

“I became one of several patients they were testing…They were experimenting with it,” Gardner later recalled.

The treatment worked. But like many patients then, Gardner entered the trial with little understanding. There were no long-term studies, no shared decisions—just trust, hope, and uncertainty.

Nearly 70 years later, the patient roles in clinical trials have changed dramatically. They’re no longer just subjects—they’ve become active partners in how studies are designed, run, and understood. A powerful example is Victoria Gray, who in 2019 became the first person in the U.S. to receive a CRISPR-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease. More than a participant, she became an advocate—using her voice to shape how future studies include and support patients.

Today, advances like AI-driven trial matching, decentralized access, and simplified, patient-friendly communication are part of a broader shift—making it easier for more people to find and join studies that match their health needs.

In this blog, we trace the milestones that made this evolution possible—and how patients moved from the margins to the center of clinical research.

1940s–1970s: The Early Push Toward Patient Protection

In early clinical research, patient protection wasn’t given, it was demanded often in response to harm. One of the first major shifts came in 1947 with the introduction of the Nuremberg Code, created after World War II to address the unethical human experiments conducted during the Holocaust. It established the essential principle of voluntary informed consent, recognizing for the first time that people have a right to decide whether to take part in research.

The Salgo v. Leland Stanford Jr. University Board of Trustees (1957) ruling in the U.S. reinforced the legal obligation to inform patients about risks associated with participation—cementing the importance of informed consent in American law.

In 1964, the Declaration of Helsinki further advanced the global framework for protecting human subjects, requiring independent ethical review and placing a special emphasis on safeguarding vulnerable populations.

Still, these safeguards were often inconsistently applied. One of the most infamous examples was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972), in which Black men with syphilis were misled and denied treatment—even after penicillin became widely available. Its exposure sparked public outrage, institutional reckoning, and urgent reforms.

By the mid-1970s, major steps were taken. The National Research Act (1974) created Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to oversee human subject research. In 1979, the Belmont Report defined the three core principles still guiding ethical clinical research:

- Respect for Persons – including informed consent and autonomy

- Beneficence – minimizing harm, maximizing benefits

- Justice – equitable distribution of research burdens and benefits

Building on these foundations, the ICH Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines introduced in 1996 established a unified global standard for ethical and scientifically sound clinical trials, ensuring participant protection and data integrity.

These changes laid the foundation for more ethical, transparent, and participant-aware research practices.

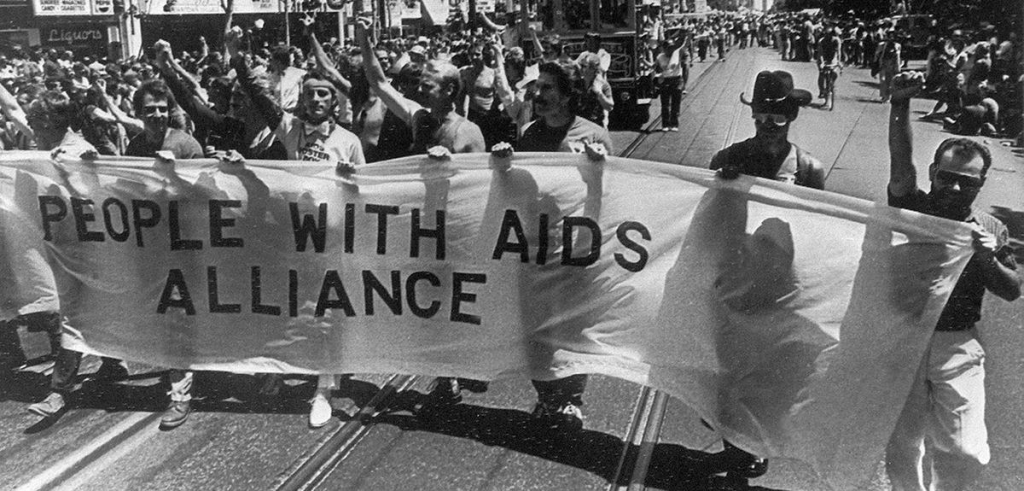

1980s–1990s: From Activism to Policy – A New Role for Patients

By the late 1970s, trust in medical and scientific authority was already shifting. Patients began asking tougher questions about consent and transparency.

Then came the AIDS crisis. Patient-led groups like ACT UP, Treatment Action Group (TAG), and Project Inform transformed medical activism into a force for accountability. These activists weren’t simply seeking access to treatments—they demanded a seat at the table:

“Nothing about us without us.” — Denver Principles, 1983

That slogan encapsulated a cultural shift: research was no longer done on patients—but with them.

Patient advocates during the AIDS crisis didn’t just reshape policy—they redefined the ethics of participation. From forcing the FDA to accelerate access to promising therapies like AZT to pushing for programs like parallel track access, they broke down hierarchies and helped establish patient experience as valid evidence.

In 1990, Dr. Anthony Fauci formally announced that activists would have representation on all ACTG committees. This was a symbolic and structural shift—from protestors outside the building to co-creators inside the room.

2000s-Present: A Major Shift Towards Partnership

The early 2000s marked a turning point. Building on the lessons of AIDS activism, patients facing cancer, chronic illness, and rare diseases moved from being participants to partners. Advocacy groups like the Michael J. Fox Foundation, Let’s Win Pancreatic Cancer, ALS Network, and SCDAA have helped build greater awareness, strengthen patient communities, and support more inclusive, patient-informed research efforts.

“Each individual knows more about their own experience than any doctor or researcher could.” — Maggie Kuhl, MJFF

In 2008, TrialX launched one of the first clinical trial apps on Google Health, marking an early step toward using technology to connect people to relevant clinical trials near them.

Global efforts like the James Lind Alliance (UK) and PCORI (U.S.) reimagined who sets research priorities—putting lived experience at the center. And by 2018, a study confirmed what many already practiced: involving patients from the start leads to better recruitment, retention, and results.

Then came COVID-19. Traditional research models were disrupted, and patients played key roles in adapting. Virtual visits, eConsent, and remote monitoring made trials more flexible—and more human.

“It was really simple, you know? They sent me the survey, I clicked right on it and filled out the information, and then it seemed like every day I’d just get a text in the morning. Then if I forgot, it would send me a reminder, which was good. So, yes. It was like a really foolproof way to make sure that they got the information across.”

— Participant 39, ACTIV-6 Study

During this shift, we helped enable decentralized research—offering tools for remote data capture, multilingual access, and study materials tailored to 5th and 8th-grade reading levels, helping broaden participation across diverse communities. As technology advanced, artificial intelligence opened new ways to engage, inform, and support patients in clinical research.

While AI in medicine dates back to systems like INTERNIST-1 in 1971 and MYCIN in the 1970s, the modern leap began in 2007 when IBM unveiled Watson. By 2011, Watson’s Jeopardy! win showcased its ability to process natural language and synthesize knowledge from vast datasets—a breakthrough soon adapted for oncology decision support and complex biomedical research. In the years that followed, AI-powered chatbots, virtual assistants, and predictive analytics began guiding participants through trials—simplifying medical jargon, providing real-time answers, sending tailored reminders, and identifying underrepresented groups for outreach.

Today, at global conferences like Patients as Partners, DIA, and DPharm, where CROs and pharma companies don’t just talk about inclusion—they demonstrate it. Patients co-present on trial design. Regulatory experts discuss how lived experience can inform evidence. Sponsors now simplify protocols and prioritize outcomes based on patient input, making trials more relevant and easier to join.

At the recent PASP EU 2025 conference, patient advocate Alfred Samuels put it powerfully:

“The patients of yesterday are not the patients of today. We are better educated, better informed – we are the partners you need. Without us, you have nothing, zilch, nada.”

But progress is not a finish line—it’s a commitment. A commitment to inclusion, transparency, and listening. As we look ahead, one thing is clear: the future of clinical research is not just more patient-centered.

It’s patient-led.

At TrialX, we’re proud to support this future—building tools that make participation more accessible, inclusive, and human. Explore our platform here. If you’re looking to participate in clinical research, sign up for our volunteer registry here.

We will be at DPharm 2025 on September 16–17 in Philadelphia, PA. Don’t miss a chance to meet our team to learn how we are leveraging AI to improve patient centricity in clinical trials.

Follow us on LinkedIn for where we’ll be sharing updates from the event.